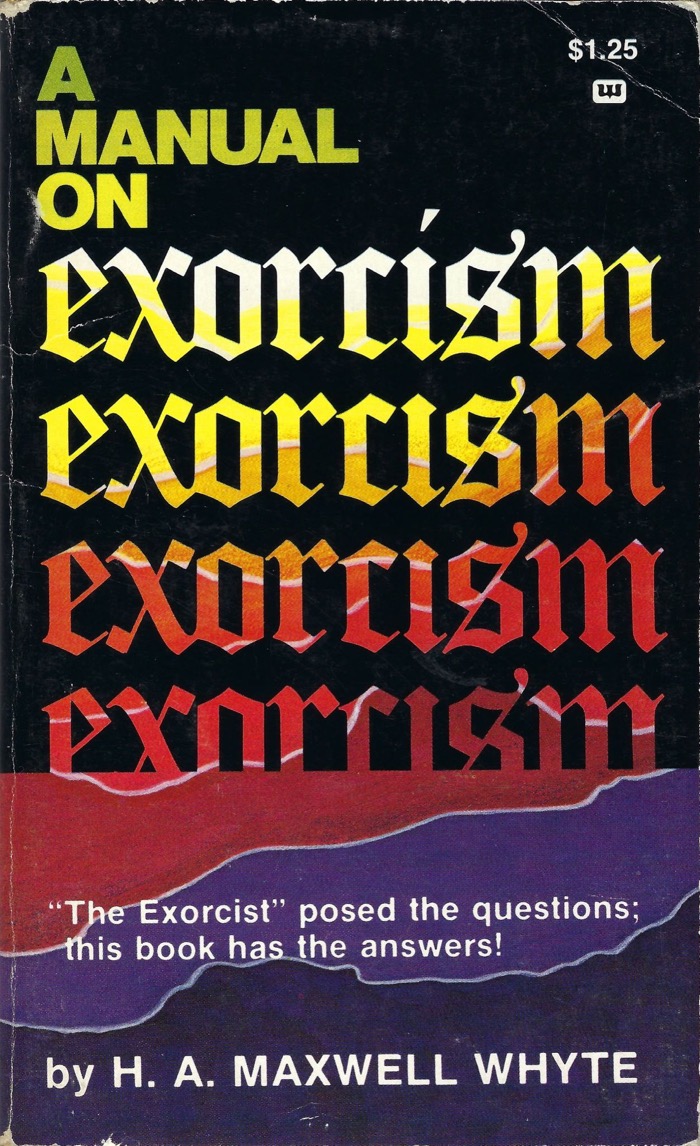

A Manual on Exorcism

Reviewed date: 2018 Nov 3

126 pages

Despite the title, it's not a manual. It's a series of questions and answers, backed up by Scripture and by Whyte's personal experience with exorcisms and confronting the demonic.

Overall, the answers and advice Whyte gives seems reasonable and grounded in Scripture. He pointed out one thing I'd missed in my recent survey of the gospels: when confronting the Gadarene demoniac, Jesus does not ask the demon its name. Jesus asks the man his name. The man replies that his name is Legion, because he had many demons. (I like that interpretation, and upon close re-reading of both the Luke and Mark accounts, I think it's the correct one. It's not the only one, though. It's possible to infer that Jesus was questioning the demons.) So it seems reasonably clear from Scripture that there's no need to converse with an evil spirit. Cast it out, rebuke it, send it away, command it to be quiet. There's no biblical example of allowing an evil spirit to speak, or of questioning it, or conversing with it.

So Whyte never talks to demons. He doesn't ask them their name. He doesn't allow them to speak or to manifest. He just commands them to leave. And because he doesn't mess about, riling the evil spirits up and giving them opportunity to show off, his exorcisms take just a few minutes. There's none of this nonsense about spending hours, of having big strong bodyguards to hold down and physically control the victims while the demons rage and thrash about. And Whyte doesn't subscribe to the whole idea of demon leaders, or captains--that is, demons who are in charge of the whole host of demons who may be oppressing a person. That concept is something that others have learned by talking to demons, so it's probably a lie anyway. That's another reason not to converse with demons. They are liars. Nothing useful comes from talking to them.

Whyte also explains that the popular understanding of demon "possession" is not really the way it works. People can have demons in them, demons oppressing them, demons vexing them. But possession in the sense of total ownership and total control, no. So then the answer to the big question is yes, Christians can be oppressed by evil spirits. And they need to be cast out.

I'm a bit unclear on how Whyte thinks demons interact with the physical world. In one place, he says demons can only interact with the physical world through a human body. (Presumably by somehow infecting or influencing the body through a person's spirit or soul?) In another place, he tells of evil spirits haunting a house and causing ghostly apparitions, which disappeared after he rebuked them and sent them away. So he's never totally clear on the abilities of demons to interact with the physical world.

He never addresses the question of whether demons have access to a person's thoughts.

Also, Whyte seems to attribute all sickness, both mental and physical, to demons. Even accidents like a broken bone? Yep, traced back to demon mischief. He suggests that people don't immediately quit taking medication after they've had their demons exorcised--sometimes it takes the body a while to return to normal, and stopping medication right away could be dangerous. But if Whyte thinks that sometimes people just get sick or get cancer or have accidents for completely natural, non-demonic reasons, he's not made that clear.

I not sure about Whyte's reference to the passage in Matthew 12, where a demon leaves a person and then gathers seven spirits even more evil than itself, and returns to the person. He referenced that as a literal mechanism of how demons work; that if a Christian backslides, they open the way for even greater demonic persecution than before. But when I read Matthew 12, Jesus is clearly talking symbolically (in parables, one might say) about judgement against Israel for not believing. "That is how it will be with this wicked generation," is how Jesus concludes the story about the demons. It isn't about demons. It's about Israel, about a "wicked and adulterous generation" that refuses to believe in Jesus. I'm sure Whyte knows this, and maybe he just didn't have space in a short book to get into the whole meaning of this particular passage.