One Against a Wilderness

Series: Kioga 3

Reviewed date: 2026 Mar 5

172 pages

One Against a Wilderness is the third entry in the Kioga series, and it's a collection of short stories about Kioga's childhood. These are boring stories.

I - The Eyes of Mialoka Will Burn Tonight

In far Nato'wa — that new-found land within the Arctic Circle — deep in the still, primeval forest called by the red-skinned natives Indegara, there stands a great rock called Chieftain's Head, supposed to be the image of Mialoka, legendary First-Chief of all the Shoni tribes. When the eyes of Chieftain's Head light up, Two-Star, the little son of Mialoka, will return to take his place among mortal men, so goes the legend, implicitly believed among the Shoni.

Kioga observes shamans Inkato and Kansa sacrifice a young Shoni boy to the Yei river spirits. Kioga and his bear companion Aki rescue the boy from the water, and Kioga recognizes him as Ohali, a boy from Hopeka. Kioga is unwilling to let this injustice stand, so he concocts a plan to return Ohali to Hopeka and take revenge on the wicked shamans.

First Kioga lights fires in the rock of the Chieftain's Head to make Mialoka's eyes appear to glow. Then Kioga disguises himself as a river spirit, takes a canoe and returns Ohali to Hopeka—not just as the boy he used to be, but returned from the dead as the spiritual reincarnation of Two-Star, son of the legendary First Chief Mialoka.

II - The Dire Wolves' Prey

On bazaar-day Kioga curls up in a wicker basket under some feather robes and overhears members of the Long-Knife Society plotting against chief Sawamic. Unfortunately, the plotters buy the basket of robes and carry it off with Kioga inside. Kioga escapes and warns Hopeka-town just in time for the warriors to rise up and defend chief Sawamic against the sneak attack.

III - Unharmed, He Dwelt Among the Forest People

Kioga finds a baby abandoned in the wilderness, and rescues him from hungry dire wolves. He recognizes the baby as the son of a chief, and attempts to return him to his village of Magua. Unfortunately, Kioga is accused of stealing the child, and barely escapes with his life.

IV - Flight of the Forest People

Kioga races against time to warn the Shoni about a flash flood that is barreling down the river towards Hopeka.

V - White Heritage

Members of the Long Knife society have murdered Kioga's adoptive Shoni parents, and as Kioga flees through the jungle he contemplates revenge. The proper Shoni response to a murder is to avenge the death by killing the man responsible and his entire family. Kioga burns with anger against those who have murdered his family and driven him from his home in Hopeka, but something inside him resists the traditional Shoni revenge.

Kioga stumbles across the wreck of the ship Cherokee, which carried his white parents to Nato'wa. In the wreck he finds various useful tools and weapons. He also finds a letter from his great grandfather Lincoln Rand, charging his son (Kioga's grandfather) to "hold life sacred," to "protect the weak," to "never strike except in self-defense," and to "never harbor hatred in your heart." This is Kioga's white heritage. He rejects the Shoni concept of revenge.

VI - The Turn of the Tide

Kioga is once again an outcast from the Shoni. He teams up with K'yopit, also an outcast, and tries to win over the men of Hopeka-town by showing them how to woodworking tools that Kioga recovered from the shipwrecked Cherokee. It doesn't work. Kioga and K'yopit barely escape with their lives. Kioga determines to quit the entire continent of Nato'wa, so he builds a boat. That doesn't work either, and he and K'yopit almost lose their lives--but they're rescued by the men of Hopeka who have used Kioga's tools and had a change of heart.

The Shores of Kansas

Reviewed date: 2026 Feb 20

Rating: 2

220 pages

Time travel

Grant Ryals has a natural ability to travel back in time to the age of dinosaurs. He uses this ability to film and produce a dinosaur documentary called The Shores of Kansas which makes him famous and wealthy besides. It's a fantastic story conceit: Grant can only travel by himself, and he can only take along whatever he can carry. To the past he takes only camera equipment, a bow and arrows, and an axe. From the past he brings back photos and videos, specimens, and occasionally dinosaur eggs or even a few living dinosaurs. Small ones, of course.

Author Robert Chilson gives us some fantastic sequences of Grant tracking a herd of sauropods, filming an attack by carnosaurs, and then watching the sauropods lay eggs on a sandbar, and, later, Grant digging up some eggs to take back with him. We also get a fantastic battle with a Tyrannosaurus Rex. The T. Rex is large and stupid, and Grant uses the creature's bulk against it, tiring it out over the course of several days until it expires from exhaustion. But the best sequence is when Grant gets in too close with a gorgosaur and barely escapes with his life.

Management woes

You'd think that the story would be a thrilling tale of survival in the savage age of dinosaurs, but no. It's a gripping tale of corporate governance woes. With the money from his first film, Grant has set up an Institute to disseminate the research data he brings back from the Mesozoic. Grant's real battles are with corporate politics in the Institute. The director, Dr. Adrian, is continually making decisions behind Grant's back: firing critical staff, hiring too many pretty secretaries, increasing the budget for public relations and book publishing while cutting science funding and restricting access to research data. Grant instructs Dr. Adrian to prioritize scientific research, but the changes Dr. Adrian promises never seem to materialize. (I think Grant should have fired Dr. Adrian.) Then there is Mrs. Cane, who is angling to get Dr. Adrian's position and may be actively sabotaging the Institute to make Adrian look bad. Things get so out of control that Grant has—*gasp*—to resort to legal threats to stop a secret Board meeting.

Thrilling stuff, this.

Woman troubles

As if that's not enough, Grant has woman problems. Specifically, his horde of adoring fans. Grant, with his trim physique and his shiny axe and his being-the-only-man-who-has-walked-with-the-dinosaurs is irresistible to women. This seems…unlikely. We're told that Grant is reclusive. His first and most famous film about dinosaurs, The Shores of Kansas, never shows him. It's his footage and he narrates the documentary, which makes him more like Ken Burns than Steve the Crocodile Hunter Irwin, but sure, we're supposed to take it on faith that Grant is the world's most famous and most desirable man.

Fortunately he turns most of these women down. Unfortunately, he only turns most of them down. There's a rich young heiress who invites Grant out on her boat and things progress as one might expect. That's distasteful but not exactly surprising. More concerning is an incident involving Grant with a farmhouse wife and her seventeen-year-old daughter that made me have to look up the age of consent laws in Kansas in the 1970s. As it turns out, that wouldn't have been illegal in 1976 when Robert Chilson published this book. As it turns out, it isn't illegal today. Kansas needs to fix its laws.

Marian Gilmore

Given his problems with women, Grant is not particularly happy that Dr. Adrian has employed another time traveler, Marian Gilmore. Marian is unable to travel as far back as Grant, but Dr. Adrian hopes that with enough training she will be able to join Grant in his trips to the Mesozoic. (This seems to be part of Dr. Adrian's attempts to bring in new revenue streams for the Institute. He has not been happy with Grant's focus on scientific research, and would like to diversify.) Marian asks for Grant's help to develop her time travel abilities, but Grant can't stand her presence, and refuses.

Emotional health

So we've established that this is not the thrilling story of survival, a man alone among the dinosaurs. But at its heart it's not the story of a man fighting corporate politics, either. It's not even really the story of a man fighting off his admirers. It's the story of a man facing his emotional trauma and coming to terms with why he has problems with women: it's the pain from a failed relationship.

Grant had been in love with a young woman named Nona Schiereck, who treated him poorly, and Grant let her go—but emotionally he was still hurt. Now, every time he sees a woman he's reminded of Nona and the painful memories. When Grant finally faces and deals with his emotional pain, he is able to move past it. The book ends with Grant realizing that he is in love with Marian Gilmore. (Fortunately Marian Gilmore loves him too, what with him being irresistible to women and all.) The two of them time-travel back to the Mesozoic together.

My verdict

Oof. No.

Time is the Simplest Thing

Reviewed date: 2026 Feb 19

Rating: 1

192 pages

I've read this one before, because I vividly remember that the Pinkness made Shepherd Blaine's mind reflective and shiny. That was meant to protect him, but in reality marked him as a big shiny target for anybody with mental powers.

The book is dull and meandering. The characters' motivations rarely made sense, and the ending was not satisfactory.

Focusing Your Church Board Using the Carver Policy Governance Model

Reviewed date: 2026 Feb 14

136 pages

OK.

When Narcissism Comes to Church: Healing Your Community From Emotional and Spiritual Abuse

Reviewed date: 2026 Feb 6

192 pages

I skimmed this one. It seems like a pretty basic introduction to narcissism. The unique thing that it offers is that it describes how narcissistic traits manifest in each of the Enneagram personality types. Given that the Enneagram is pseudoscientific nonsense with no grounding in research, I'm not sure how valuable that is. But I guess it can help by showing different ways that narcissism can show up in different people.

Space Relations

Reviewed date: 2025 Nov 15

Rating: 2

248 pages

A middling science fiction novel. I read it because I know another, unrelated, Donald Barr and I found the coincidence of names amusing.

The Arsenal Out of Time

Reviewed date: 2025 Nov 7

Rating: 2

156 pages

This one was OK.

Rogue Queen

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 26

Rating: 3

189 pages

It was fine. I didn't write a detailed review, but I noted some key words as I was reading.

Iroedh

Antis

Vardh

Dr. Bloch

Daktablak

Rhodh

Queen Intar

Avtiny

Princess Estir of Elham

duel

machete

Agent of Vega

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 23

Rating: 1

185 pages

A fixup. Schmitz's writing is infuriating as always. He leaves out important bits of information to ratchet up the suspense, but the result is in three out of the four stories I never could satisfactorily figure out the plot. Big thumbs down from me.

Day of the Giants

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 20

Rating: 3

128 pages

Leif Svensen is kidnapped by Loki and taken to Asgard where he's put to work designing weapons for the Aesir to use against the giants when Ragnarok comes. With the help of clever dwarfs, Leif produces gunpowder grenades, explosive-tipped arrows, and fission bombs. Oh yeah, the dwarfs can refine U-235, don'tcha know?

It's books like these that reveal my almost-complete ignorance about Norse mythology. I'm sure there was a lot I missed out on.

del Rey writes well and Day of the Giants is engaging. I'm labeling this science fiction because it feels like science fiction, even though there's magic and this is clearly fantastic.

Starswarm

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 19

159 pages

Starswarm is a collection of stories set in the same universe. The stories vary in style and do not fit into an overall narrative. Therefore I'm categorizing this as a collection rather than a fix-up novel.

My enjoyment of the stories varied widely. A Moon of My Delight is heartbreaking and may be the best story I've read all year. Shards is drivel. The rest are somewhere in between, but on the whole, they weren't my sort of story.

Sector Vermillion

a kind of artistry

Derek is an Abrogunnan which means he’s brave and competent, enough to make first contact with an alien life form and win the admiration of the elites of the Starswarm—but he’s an Abrogunnan which means his life is ruled by a matriarch who he serves as little more than a slave.

Sector Gray

hearts and engines

A colonel in an eternal war dreams of going on a mission and returning to meet a woman. But there is no woman and he is only a sergeant.

Sector Violet

the underprivileged

Saton and Corbis, immigrants from

Istinogurzibeshilaha, arrive on the planet Dansson, where nobody is ever unhappy. They are inoculated against unhappiness by the immigration agent and taken to live in Little Istino, where—being happy—they don’t realize they are basically preserved specimens in a cage. The planet Dansson is museum/zoo, collecting all endangered species in the galaxy.

Sector Diamond

the game of god

On the planet Kakakakaxo, cayman-headed natives keep two kinds of pets, dubbed bears and pekes. But who is the real intelligent species on Kakakakaxo?

Sector Green

shards

Six pages of incomprehensible dribble about creatures in Mudland is explained in the final two pages: this is an experiment to adapt humans to live as aquatic creatures so they can infiltrate a group of invasive, aggressive aquatic aliens who have take up residence in Western Ocean and threaten the human residents of the planet.

Sector Yellow

legends of smith's burst

Stranded on the backward planet Glumpalt, a trader must escape from slavery, find his way to Ongustura and catch the only spaceship headed off-planet. On the way he encounters raiders, magicians, antigravity rocks, a warlord and his daughter, and of course the Black Sun whose dark rays smother all light from Glumpalt’s three other suns.

Sector Azure

a moon of my delight

The planet Tandy Two’s entire equator is ringing with a braking system for FTL spaceships. It’s an ingenious idea, and the poignant, sad story that Aldiss writes about the people who live in its shadow is the best story I’ve read all year.

The Rift

old hundredth

On an earth populated by the resurrected recreations of extinct animals, a megatherium (giant sloth) named Dandi Lashadusa wanders around riding a baluchitherium (giant hornless

rhinoceros) and communicating telepathically with a blind Mentor who we later learn is a dolphin. She fights a bear, abandons her relics that came from humans, and turns herself into music. This story is so dumb.

A Choice of Gods

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 17

Rating: 2

176 pages

All but a few hundred humans vanish from the face of the Earth. The remaining few are now almost immortal, and they do well with their robot servants, but without sufficient population they must live without technology. As a result, they develop their latent mental skills, which includes telepathy and interstellar teleportation. Most of the remaining humans go jumping around the galaxy, exploring. Only a few stay behind.

There's some fuss about a strange intelligence located at the center of the galaxy, and there's some to-do about the robots (most of whom have no humans left to serve) building a giant super-computer robot brain to help them figure out the meaning of life or something. Also, it turns out the eight billion missing humans are alive and well on three planets far, far away from Earth. The strange intelligence had transported them there as some kind of experiment. The real experiment seems to be what the robots will do, though. I think (I'm not sure, it was unclear) that the strange intelligence is more interested in the robots than in the development of humanity.

Altogether a disappointing book. I usually like Simak, but not this one.

Planetary Agent X

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 15

Rating: 3

133 pages

Ronnie Bronston is a newly-minted agent of Section G of the United Planets (UP) Bureau of Investigations. As a member of Section G, it's his duty to enforce articles 1 and 2 of the UP charter:

Article One: The United Planets organization shall take no steps to interfere with the internal political, socio-economic, or religious institutions of its member planets.

Article Two: No member planet of United Planets shall interfere with the internal political, socio-economic or religious institutions of any other member planet.

Bronston's first assignment is to uncover the identity of Tommy Paine, an elusive individual who has been traveling to various planets and meddling in their internal affairs by starting revolutions, assassinating politicians, undermining confidence in local gods, and so forth. If it becomes known that someone is meddling in other planets' internal affairs—and that the UP hasn't been able to stop it—it could undermine confidence in the UP itself.

Bronston tracks Tommy Paine across several worlds before he realizes that no one person could possibly do everything Tommy Paine gets credit for. The real Tommy Paine is an organization. The real Tommy Paine is Section G. And now that he knows the big secret, he can begin his real job: to violate the UP charter and meddle in the internal affairs of member planets to prevent stagnation and force technological advancement. Section G knows something that the member worlds don't: there are at least two hostile alien races in the galaxy which mankind has not yet made contact with, and Section G's job is to ensure that when contact is made, mankind is ready to defend itself.

In the second half of the book, Bronston hunts a mafia hitman and manipulates him into going back to kill his old mafia boss.

The Rival Rigelians

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 14

Rating: 2

132 pages

A group sets out from Earth to Rigel, where they will secretly influence events on two lost colony worlds to bring their civilizations up to the point where they can join the Galactic Commonwealth. A disagreement on how to proceed sharply divides the group, so they agree to split their forces: one group will work on the planet Genoa and use capitalistic means; the other will bring communism and a command economy to the planet Texcoco. Who will win? Which planet will advance faster?

The events on Texcoco involve a lot of bloodshed to unite the disparate tribes and force them to industrialize. On Genoa there are problems too: unbridled capitalism brings winners and losers as well. But in the end, it's the Rigelians who are the winners: they realize they are being manipulated, and the two planets develop enough space travel to visit each other, join forces, and kick out the interloping Earthers. Genoa and Texcoco will develop their own economic and political systems, thank you very much. Earthmen, go home.

Cycle of Nemesis

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 13

Rating: 1

190 pages

Spectres at the Gannet estate sale

Bert and his friend George Pomfret are attending a grand estate sale at Gannets. Pomfret, representing a private club of wealthy art collectors, wants to buy a Bernini Aphrodite; Bert has his eye on an antique globe. As Bert wanders around Gannets he experiences disturbing apparitions: a mysterious man wearing his own face appears, disappears, reappears dressed in ancient period costume, then disappears again. Is he going mad? Later, the auction is interrupted when an antique cabinet is opened for the watching bidders—and the decapitated body of a young woman rolls out.

A girl's body, naked, decapitated and smothered in blood, sprawled laxly before us.

When Bert returns to Gannets the next day he still sees strange things, but this time he's not the only witness. He strikes up a conversation with a young woman named Phoebe Desmond, and they both witness a red-haired woman running down a hallway being pursued by a demon from hell.

Toward us over the dark planks ran a naked girl, her long reddish-blonde hair streaming out behind her, her arms imploring succor, her mouth open and red and gaping. Following her in a crouching loathsome waddle and yet covering the ground with ferocious speed ran a—I did not have the words to describe it. Furred, fanged, ferocious, feral. With deep crimson pits for eyes and with thick and heavy iron boots strapped to its feet, each boot—there were four of them—tipped with a long, sharp, ugly and obscene spike, the thing squattered over the floor after the girl."

Both the girl and the iron-booted monster vanish into thin air.

I wish to point out that we've scarcely begun the story and author Kenneth Bulmer has already introduced us to two naked women whom he refers to as girls, one of whom is fleeing from a literal monster and the other who has been gruesomely murdered. This seems borderline prurient at best. It's certainly unnecessary. Fortunately this is about as bad as it gets.

The globe

Bert wins the auction for the antique globe. A late-comer who just missed the auction approaches Bert and offers—nay, demands—to buy the globe from him. Bert is intrigued and eventually agrees to sell, but only if the man explains why he desires the globe.

Khamushkei the Undying

The mysterious late-comer introduces himself as Hall Brennan, and explains that he's an archaeologist on the trail of an ancient mystery. Millennia ago—so the ancient writings say—the great god Khamushkei the Undying destroyed the face of the earth. His children Mummusu and Shoshusu imprisoned him in a Time Vault, sealed with curses and spells. The final spell was incomplete, so Khamushkei was not imprisoned for all eternity, but only for about seven thousand years. Coincidentally, it's been just about seven thousand years, so Khamushkei is due to break free any day now. Brennan believes the globe contains clues to the location of the Time Vault, and he hopes to locate the vault and prevent Khamushkei the Undying from escaping.

Everyone seems quite interested, so they all agree to help Brennan. The globe does indeed contain clues: a "compilation of ritual curses", and a location in the desert southwest of Baghdad. The party consists of:

- Hall Brennan

- Bert

- George Pomfret

- Charlie, George's robot butler

- Phoebe Desmond

- Paul Benenson, an odious rich friend of Pomfret

- Lottie, Benenson's red-headed secretary

Bert and Phoebe immediately recognize Lottie as the red-haired woman they saw running from the iron-booted demon monster. Lottie seems to be clueless, so there's some weird time travel shenanigans, but the upshot is: things are not looking good for Lottie.

Showdown and sacrifice

Khamushkei the Undying may be locked in his Time Vault, but the seals are weakening and he is certainly capable of sending minions to do his bidding. Our heroes battle mythical creatures such as lamassu, utukku, and griffins. Khamushkei the Undying tries to throw them off track by sending them back in time, to ancient Sumeria. At one point Khamushkei even accidentally transports them back inside his Time Vault where they get a good look at how things are organized.

In the final showdown, Khamushkei the Undying figures that the way to stop Hall Brennan and the others is to steal the globe before they can open it, which is why he transports them and all his monsters to Gannets. That's where all the apparitions came from. It's a close thing, and yes, it is Lottie being pursued by the iron-booted demon monster. Our heroes use the compilation of curses from the globe to lock Khamushkei back in his Time Vault, but to make the curses effective requires a sacrifice. It's Phoebe who selflessly makes the ultimate sacrifice, and it's her decapitated body that we saw in the opening chapter.

Interesting. Bulmer killed off the plucky heroine and let the bombshell secretary survive.

The world is safe from Khamushkei the Undying for another seven thousand years.

Space Gypsies

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 12

Rating: 3

128 pages

This is your basic humanity vs genocidal chlorine-breathing slug monsters for control of the galaxy. It's a lot of fun.

Howell owns a little spaceship, Marintha, and he's hired himself out to take a botanist, Breen, to various worlds to take samples of progenitor food-plants. Howell is doing this mainly because Breen is accompanied by his daughter Karen. Also on board is Marintha's engineer, Ketch.

Marintha has no weapons, because as author Murray Leinster points out, humanity is secure in the knowledge that there are no alien civilizations out there. The only thing mankind has found, on planet after planet, are rubble-heap cities. These smashed cities are all that's left of an ancient civilization of humans that disappeared forty centuries ago. As Leinster points out, nobody thinks to wonder who smashed those cities and what happened to those humans.

Ha. Deep in interstellar space Marintha is attacked by slug-shaped alien spaceships. The slug-ship creatures very much want to kill all humans. Marintha escapes badly damaged; Howell makes a landing on a nearly habitable planet to effect repairs.

There's a lot more. On the planet Howell and the others make contact with another race of humans. These humans, clearly descended (like people on Earth) from the progenitors, have spent generations battling the slug-ship beings. They live in spaceships as gypsies, running from planet to planet. They are small, which is useful for living in the limited space on board their spaceships: adults are the size of a twelve-year-old child. Howell and the others can't communicate with the other humans—there is no time to learn each others' language—but using gestures and sketches they do the best they can.

Howell is frantic to ensure that the slug-ship creatures don't learn about Earth. These creatures destroyed the progenitors' cities, and they have been methodically hunting and exterminating the space gypsies for thousands of years. If they find out there is another civilization of humans, they'll come to an unsuspecting Earth and wipe it clean of life.

The slug-ship beings are chlorine-breathers, and they've developed advanced plastics which they use to coat every bit of metal on their spaceships, because otherwise the corrosive chlorine atmosphere will destroy the metal. It's that plastic construction that proves their downfall.

The space gypsies are overjoyed when they see the molecular disintegrator garbage unit on Marintha. They demand he show them every specification and schematic for every part of the garbage unit. Howell can't figure out why. It's just a garbage unit, it generates a waveform that disintegrates anything carbon-based like food waste.

And plastic. Plastic is carbon-based.

The space gypsies figure it out first, but Howell eventually figures it out. He hooks the garbage unit to Marintha's hull and uses the entire metal surface of the hull to broadcast the destructive waveform. Any slug-ships that come near are hit with the waveform and immediately fall apart as the plastic in their plastic-and-metal hull disintegrates.

All humanity is saved. Humans rule, chlorine-breathing slug-ship creatures drool! The end.

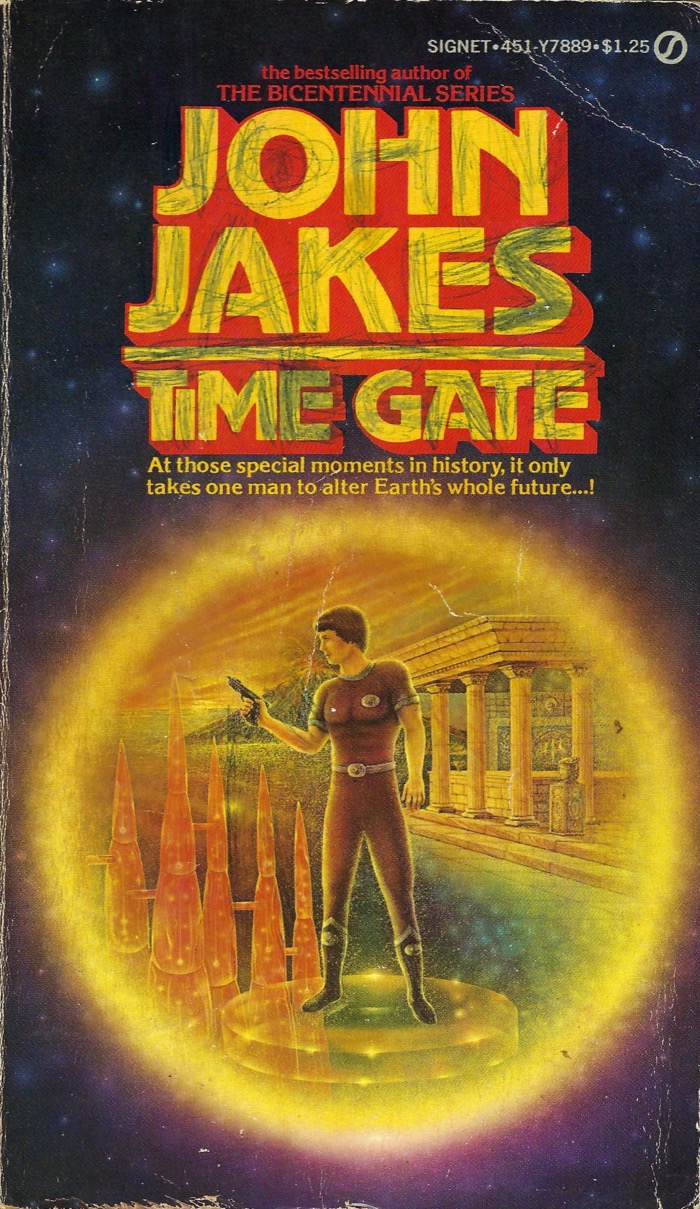

Time Gate

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 11

Rating: 2

149 pages

Someone has scribbled on the cover of my copy of Time Gate. That's disappointing. Fortunately it hasn't obscured any of the artwork. Time Gate is a time travel story (I don't care much for time travel) and it's a mildly interesting read. Author John Jakes is a decent storyteller.

Secret government lab

The US government has a secret time travel lab. They use it conscientiously, only visiting and observing past events, never interfering. The biggest problems are firstly that Tom Linstrum chafes under the overbearing guidance of his older brother Dr. Calvin Linstrum. (Their late father invented the time machine, so both brothers are carrying on his work.) And secondly, that an investigative reporter named Sidney Six has discovered the existence of the time travel project. Vice President Ira Hand himself pays a visit to the lab to warn the staff to be on alert for a reporter trying to infiltrate the lab.

Blame the intern

Donald Koop is an intern working on the time travel project, foisted on them due to his uncle's connections. His uncle is a Senator. Koop is a radicalized right-wing ideologue who's convinced that President Archibald's proposed disarmament policy will lead to disaster. Furthermore, Donald is willing to do something about it. He grabs an unlicensed laser pistol, sneaks into the lab on his day off, and sets the time machine for March 12, 1987 to assassinate Archibald.

Pompeii, A.D. 79

Donald is not very smart and doesn't realize how the time machine works. He ends up in Pompeii a few days before Vesuvius is set to blow. Tom, Calvin, and Dr. Gordon White go back to Pompeii and spring Donald from a Roman jail. (It turns out Donald wasn't very smart in ancient Rome, either, and had gotten himself arrested.) They bring him back to the present.

The intern, again!

None of our heroes is particularly quick-thinking, so they let the intern get the drop on them again. Donald grabs a laser pistol, forces everyone into the vault and sets the timer to keep the door locked overnight.

Sidney Six

It's at this point that we learn Sidney Six is a floating mechanical device, "an artificial news gathering intelligence." It's an autonomous robot reporter drone that flies around and gathers news. He's infiltrated the lab packed into some supply crates. Donald puts Sidney Six into the vault along with the rest of the crew.

Sidney Six is an interesting idea, but he doesn't actually play into the plot.

The intern changes history

Donald correctly sets the time machine, travels back to March 2, 1987 and assassinates Archibald, then jumps forward to 3987.

3987

Everyone now remembers that President Archibald was indeed assassinated. Tom, Cal, and a few others also remember that he wasn't. They brief President Hand on the events, and he authorizes them to apprehend Donald and to (if possible) to back and restore the proper timeline. Cal, Tom, White, and Sidney Six travel to 3987 where they find a dying earth and the last few humans—a technologically advanced civilization, but one that has been slowly dying due to the effects of a nuclear war started in 2080. Without Archibald's disarmament plan, the Asiatics launched a planet-killer nuclear weapon which rendered much of the globe uninhabitable and most humans infertile. The race has survived, barely, until 3987 but their numbers keep dwindling; they are within a few generations of extinction. It's imperative that Archibald be allowed to live.

The group locates Donald in 3987, and Donald dies in the ensuing firefight.

1987 and 2080

Cal and Sidney Six travel back to 1987 and stop the assassination. Donald dies again. Archibald lives. But back in 3987 nothing has changed. The planet and the human race are still dying. The Asiatics still set off their doomsday machine in 2080. Cal has been injured, so Tom and a few others travel to 2080, sneak into the doomsday machine headquarters and sabotage it. The world is saved. Back in 3987 the earth and humanity are flourishing. Tom, Cal, and everyone head back to their own time. The end.

Subplots

There was a romantic subplot wherein Tom falls in love with Mari, a young woman from 3987. She accompanies him to 2080 to disable the doomsday machine, so her 3987 is unrecognizable when she returns. She goes with Tom to 1987 instead.

The other subplot is the conflict between Calvin and Tom. Calvin is overbearing and tyrannical in his dealing with everyone, especially Tom. By the end of the book Tom has gained confidence and broken free from Calvin. It's not that Calvin has changed, but rather Tom who has matured: he's grown up, independent, and no longer needs Calvin's approval or permission for his choices in life.

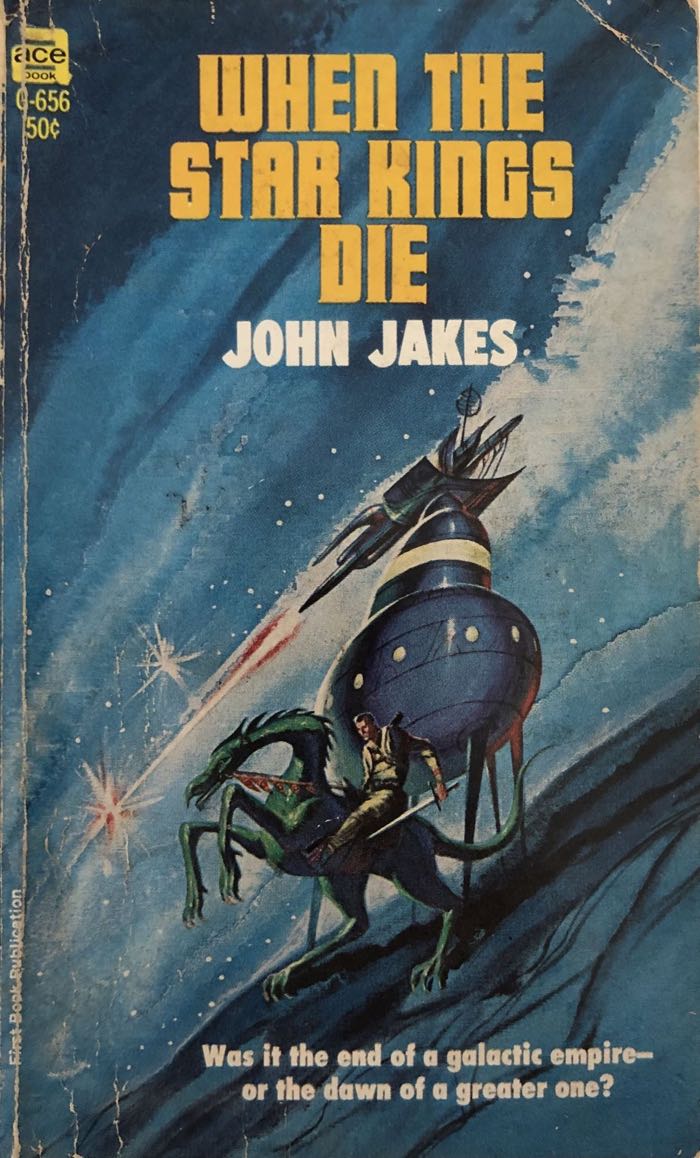

When the Star Kings Die

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 10

Rating: 2

162 pages

Star King

I confess I read this one simply because I've already read Star King by Jack Vance and The Star Kings by Edmond Hamilton. Well, that and the Jack Gaughan cover art. This one is a fairly paint-by-numbers adventure, I'm afraid, but it's well-done for what it is.

The Star Kings: an infodump

We start out with a little infodump.

See, then, II Galaxy.

It wheels and a billion stars wheel with it, far in space from the First Home, the Earth, far in future time from the Out-riding in the lightships, that now-ancient history which carried man out past the point of returning, to where he could become, without aid from the First Home, the master II Galaxy.

In II Galaxy, savagery and opulence live side by side in an uneasy tension on planet after planet. Common people of all the star races, Terran and otherwise, grub out existence in near-primitive surroundings, ruled by the loose confederation of ageless, deathless star kings—

The Lords of the Exchange.

Those Lords of the Exchange are the star kings, and they're descended from ancient Earth corporations. For example, there are Genmo and Fomoko and Unilev and Mishubi. It's a little odd that corporation names are still around, even more so that they've all morphed into hereditary dictatorial fiefdoms. The star kings are practically immortal, living eight or nine hundred years.

Also odd is that everybody, and I mean everybody, talks about II Galaxy, or more often, simply, II. That's such an awkward turn of phrase.

Dragonard

Our hero Maxmillion Dragonard is a Regulator, which is what they call policeman in II. (See how odd that is? Who talks like that?) Or rather, he's a former Regulator: Dragonard is subject to fits of what he calls the redness. Dragonard bemoans this medical disability, which he claims is a brain problem that causes him to lose control of his emotions and go into uncontrollable rages. It's completely out of his control, and in one rage he beat a suspect to death. That got him sent to prison, as it should! Dragonard is now serving a life sentence on the prison planet Rankor.

Prison break

You can't keep a Dragonard in prison though. He and fellow inmate Tingo Spellhands stage a daring escape, which almost works. It doesn't, though. But surprise, just as Dragonard is about to be recaptured he is rescued by his old Regulator colleagues.

The Regulators sprang him from prison? Sure! His old boss, Sectioner Jonas Valk, explains: the star kings are dying young and nobody knows why. It's been hushed up, but something is afoot, and it might have something to do with a small rebel group called the Heart Flag movement. Someone needs to investigate, and it's got to be done off the books, so Dragonard is the man for the job. His friends set him up with money, clothes, and forged identity papers, and send him off on a spaceliner bound for the planet Pentagon where he is to meet up with the Heart Flaggers and figure out what's going on.

The redness

Dragonard makes a big deal about how his fits of redness are a medical disability and completely out of his control. I'm not so sure. The redness only rises when Dragonard puts himself into highly charged, violent situations. For example, after he boards the ship to Pentagon to start his secret mission, the first thing Dragonard does is head to the casino, chat up a girl, and then join a high-stakes game of dice. He loses. He gets angry. He catches a player cheating. He violently confronts the player and starts a fight. The other guy fights back. Then the redness comes upon Dragonard: he loses control and nearly kills the guy.

Yeah…Dragonard doesn't have a medical condition: he's just an angry, violent man who makes poor choices. He should be in prison.

High Commander Thomas St. Anne and star king Mishubi II

Dragonard is bad at undercover work. On Pentagon he immediately gets picked up by the authorities and brought before the boss of the Regulators, High Commander Thomas St. Anne. Dragonard thinks this is a good thing, but quickly realizes that whatever the conspiracy is, St. Anne is in on it. St. Anne and the star king Mishubi II are conspiring together, and they throw Dragonard into a dungeon beneath the Fortress Starmarch.

Kristin, Jeremy, Bel, and Methuselah

Dragonard makes a friend in prison: a young man named Jeremy Lynx. With help from a young woman named Kristin (who he had previously met on the spaceship en route to Pentagon; Kristin works for St. Anne but is clearly smitten with Dragonard) and with coordination from outside forces (the Heart Flag movement attacks Fortress Starmarch), Dragonard and Jeremy escape and join up with the Heart Flaggers. Jeremy reveals that he is actually Methuselah, the leader of Heart Flag. Jeremy introduces Dragonard to his sister, Bel, and now Dragonard has two love interests. One of them is surely going to die.

Showdown at Kalrath

Jeremy is coy at first, but eventually reveals that the Heart Flag movement has seized control of Kalrath, a secret medical facility deep in the North Wastes of Pentagon. It's the organ bank facility where star kings go to get transplants: new kidneys, new lungs, new intestines, new skin, new blood, new hearts and livers and eyes and brains. It's medical technology that the star kings have long claimed is lost, but which in reality they've been hoarding for themselves for thousands of years. They can do more than transplants, too: they rebuild Dragonard's brain cell-by-cell and correct the error that causes the redness. He's cured.

Mishubi II and St. Anne attack the Heart Flag army with a detachment of Regulators, and are beaten back. Mishubi changes tactics: he agrees to discuss terms. Jeremy lays out the plan: the Heart Flaggers will retain control of Kalrath for five years, during which time the star kings will "discover" the secrets of organ transplant and life extension, which they can benevolently give "to all the people of II." (Once again, who talks that way?) When "every adult and child in II Galaxy can be reborn medically the same way the Lords are reborn," Jeremy will give Kalrath back. Mishubi, representing all the star kings, reluctantly agrees.

It's a trick, of course. During a dinner celebrating the successful negotiations, St. Anne has Kristin dance for everyone's entertainment. She slips and falls on a knife which St. Anne has been carelessly and drunkenly waving about. While everyone is distracted trying to get Kristin down to the organ banks to save her life, Mishubi and St. Anne's forces sneak into Kalrath and retake the facility.

Jeremy is mentally broken by the defeat. Dragonard takes the initiative and singlehandedly re-infiltrates Kalrath, stabs St. Anne to death, plants a bomb, and blows the whole place up. Kalrath is gone, the life-prolonging medical technology is gone, Mishubi is dead, and without the organ banks, the rest of the star kings will soon die. Kristin also is dead.

Denouement

Dragonard is certain that when the Heart Flag movement tells II Galaxy about Kalrath and the organ banks, the knowledge that medical life extension is possible will spur research and the technology will soon be rediscovered. Long life will belong to everyone in II Galaxy.

Dragonard mourns for Kristin. Bel is wise enough to let him do so, and to let him know that she will be right there by his side when he's ready.

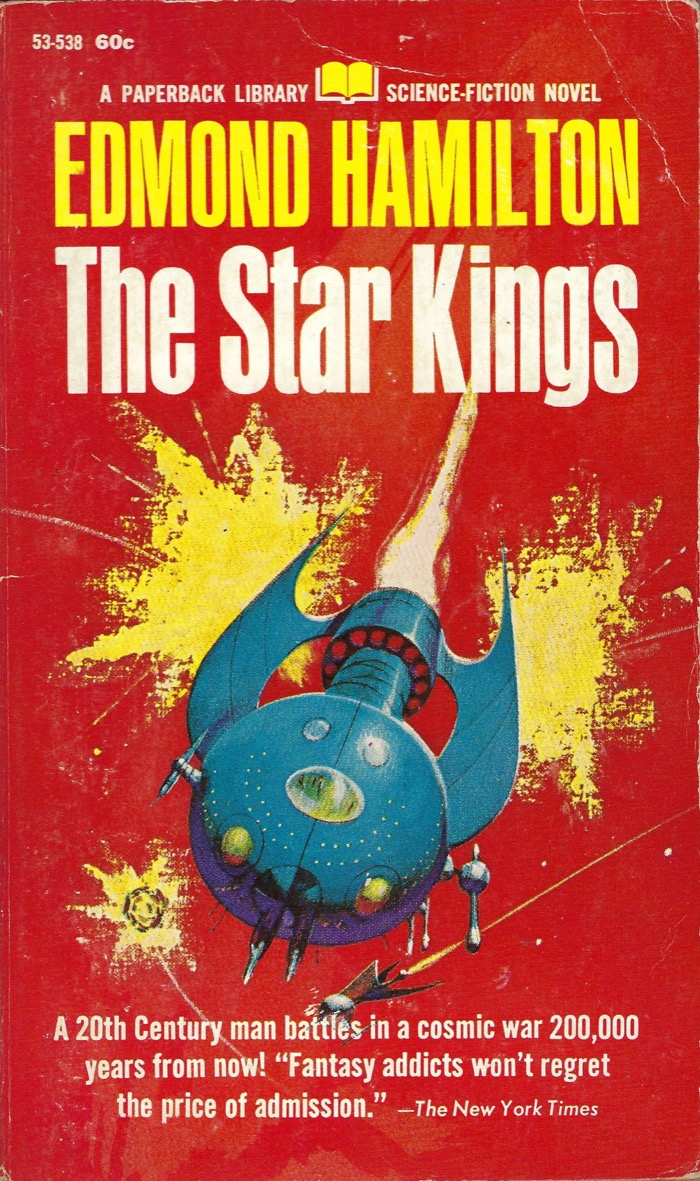

The Star Kings

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 8

Rating: 2

190 pages

This rip-roaring space opera. It's Buck Rogers stuff. Boring desk-job John Gordon swaps minds with Zarth Arn from the year 202,115. In the 200th millennium Gordon-as-Zarth Arn finds himself a prince of the Mid-Galactic Empire. He wins the heart of a princess, fights a galactic war against the evil League of Dark Worlds, and looses the awful power of the Disrupter—a weapon with the power to rip apart the very fabric of the galaxy itself!

It's not high-brow literature, and it's very much space opera, pulp-era proto-science fiction. That's fine, and it's a satisfactory story. I'm not sure I'll seek out a sequel though. This kind of story is enjoyable, but it needs a special quality of writing, something that (at his best) Edgar Rice Burroughs could provide but which is lacking here. The Star Kings goes through all the motions and hits all the proper plot points, but that's what it feels like: that it's going through the motions and hitting the proper plot points. It doesn't move my soul like ERB's John Carter stories.

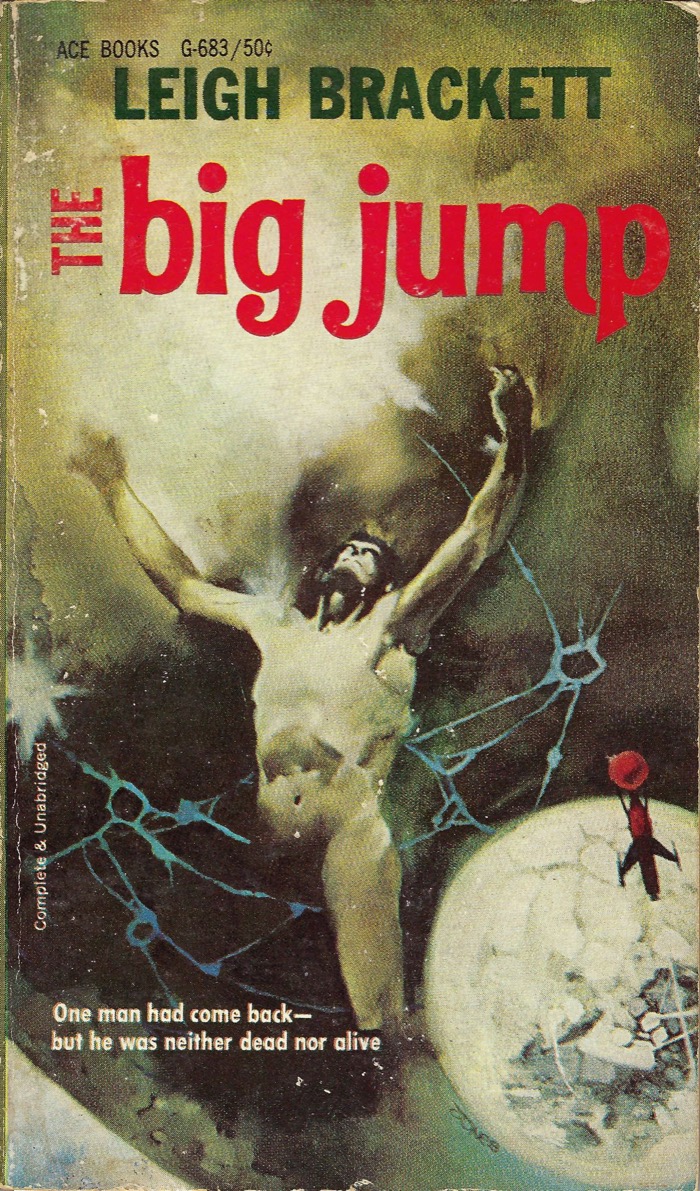

The Big Jump

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 7

Rating: 2

128 pages

My verdict: an overall disappointing book. It starts out exciting, but ends up with woo-woo pure life energy nonsense.

Good friend

Arch Comyn is a good friend. When Comyn gets wind that Ballantyne has returned from his Big Jump (that is, his experimental faster-than-light spaceship worked, and he's returned from Barnard's Star), Comyn forces his way into the high-security corporate hospital where Ballantyne is being treated and questions him. Because Ballantyne returned alone, and Comyn would like to know what happened to his friend Paul Rogers who was on Ballantyne's inaugural Big Jump voyage.

Transuranae

Ballantyne whispers a few words to Comyn and then dies. Comyn is in big trouble with the Cochrane family corporation that bankrolled Ballantyne's trip, but only Comyn knows what Ballantyne revealed, so he parlays that into a deal with the Cochranes: Comyn tells what he knows, and in exchange he gets to go on the second Big Jump out to Barnard's Star to see what Ballantyne found. Comyn also becomes very friendly—very friendly—with Miss Sydna Cochrane.

What Ballantyne found was transuranic elements. The scientific and business opportunities of these new elements are boundless. But Ballantyne found something else, something that scared him to death and likely caused the demise of his crewmates: the Transuranae. Comyn isn't sure what or who the Transuranae are, but clearly that is danger at Barnard's Star.

Woo woo life energy

The answer is disappointing. The Cochranes outfit a new spaceship and everyone travels to Barnard's Star and lands on a habitable planet rich with transuranic elements. The transuranic elements are energetic, with a kind of life energy. This lures people in like a drug, and that's what happened to the rest of Ballantyne's crew: they were turned by the transuranic energy and joined the Transuranae, who are beings of pure energy or some such nonsense. Most of the Cochrane crew gets turned into transuranic energy zombies too. Comyn escapes back to Earth and ends up with Sydna Cochrane.

The Dark Millennium

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 6

Rating: 1

143 pages

Poignant and harrowing

The book starts out with a series of poignant and harrowing scenes depicting the outbreak of nuclear armageddon. Ilse Walchern and her friend Carl Seeborg on holiday at resort town of Ustka on the Baltic Sea; pilot Simon Marks having a beer in Brooklyn restaurant; Vladimir Omolov running away into the Ural wilderness because he saw the rocket launch and knows the retaliatory strike is inevitable; Paul Mayhew and Patricia Corday in love on a trip to Italy, looking out at the Mediterranean Sea and the Faraglioni rising out of the dark waters; blind Stephen Norcross bravely emerging from an underground bomb shelter in London to face the end of all humanity. Author A. J. Merka is supremely talented; the scenes are poetic and heartbreaking, they remind us of the best of humanity when the world is experiencing the nuclear war caused by the worst of humanity.

It's a shame the book is so rotten.

Mr. Merak can turn a phrase with the best of them, but the storytelling and the plot of The Dark Millennium is complete trash.

Abducted by Vorzans

All seven of the characters introduced in the vignettes survive the nuclear armageddon. They are the only survivors. An alien race called the Vorzan abduct them and put them into suspected animation. The Vorzan wish to colonize Earth, but to do so they must be sure that the effects of planet-wide nuclear war have dissipated and the planet is safe to live on. To that end, they'll drop a couple of their human test subjects onto the planet every two hundred years or so and see how they fare.

That makes no sense, and Simon Marks even calls them out on it: "Wouldn't it be far simpler to send [instruments] down at regular intervals? Surely you can measure the radiation, the composition of the atmosphere and anything else you might need." But no, for plot reasons the Vorzan must send our heroes down as guinea pigs.

First awakening

Marks and Norcross are sent down first, after 250 years in suspended animation. They land right in a radioactive hot zone: the pulverized remains of a bombed city. After a day of walking they get to safer land, but it's too late. They've both received lethal doses of gamma radiation and die in horrific pain.

Second awakening

At the 700-year mark the Vorzans send down Ilse Walchern, Carl Seeborg, and Vladimir Omolov. They don't perish from radiation poisoning. Instead, they find a city built by mutants, which presumably are the descendants of humanity who survived the nuclear war. Never mind that we were reliably informed earlier in the book that these seven people rescued by the Vorzans were the only humans left alive. Now there is an entire civilization of mutants. (Mutants who, after 700 years, still speak recognizable English, but never mind.) They never meet the mutants, mind you: the mutants attack them, there's a shootout with laser guns, and Walchern, Seeborg, and Omolov die in horrific pain as energy weapons "[lick] through [their] lungs like an inferno wind."

Third awakening

After nearly a thousand years, the Vorzans revive Paul Mayhew and Patricia Corday. This time the Vorzans give them a pinnace and allow them to fly it around and explore the whole planet. Mayhew figures if any humans are still alive, it would be in Antarctica because it's the only continent that wouldn't be bombed into radioactive oblivion. That makes no sense at all. Nobody can live in Antarctica because it's a frozen desert.

But what do you know, he's right! Paul and Patricia find a thriving city of regular non-mutant humans living under the ice in Antarctica. Paul warns them about the Vorzan fleet that's in orbit, poised to begin colonization, and explains how to defeat them. They gather up a few nuclear warheads and fly to a remote island in the Pacific to turn those warheads into weapons capable of defeating the Vorzans.

Fortuitously, on this Pacific island they find a huge tower constructed centuries ago by mutants. There are no mutants anymore, though. It appears mutants have died out. Conveniently. Also conveniently, the mutant tower is filled with "row upon row of sleek-bodied missiles." Very nice. They rig the missiles up with their nuclear warheads and launch them into orbit, where the missiles destroy all the Vorzan spaceships.

All but one, that is. The Vorzan flagship. The big one. The invincible one. The one that can detect and avoid any nuclear-tipped missiles that are on the prowl for it. But—ooops!—it can't detect non-nuclear threats. An old satellite, Explorer VII, launched back in 1969 and swinging around in Earth orbit ever since, coincidentally and conveniently smacks into the Vorzan flagship and blows it all to pieces.

The end

I hate this book so much.

Space Lash

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 5

206 pages

Formerly published as Small Changes

I very much enjoyed "Trojan Fall". Stories that rely on hard scientific knowledge are fun. The best story in the collection is Raindrop.

Dust Rag

Two astronauts on the moon take an exploratory walk in a crater, and due to particular magnetic effects triggered by a solar storm they find themselves in a fine cloud of suspended moon dust. It's amusing until the charged dust particles adhere to their visors and block their vision, at which point finding a way to reverse the static charge and clear their vision is a matter of life and death.

Sun Spot

A crew of scientists burrowed into the inside of a comet make a brave transit around the sun to get a close-up look at the sun. When unforeseen trouble with their equipment threatens to render their main camera system useless, "Grumpy" Ries takes a crew to the comet's surface and makes repairs, risking his life for science.

Uncommon Sense

Laird Cunningham has deliberately crashed his ship and run off into the hostile, airless landscape to escape from the mutinous crew who would kill him to steal the ship for themselves. It's only a matter of time--a day or two--before they fix the ship, and Cunningham can't survive on an airless planet, so he must figure out a way to distract the others so he can retake the ship. Meanwhile, he sits in a cave and watches the bizarre local life forms: crab-like creatures with liquid metal blood that feed on what serves for local "plant" growth, and large, aggressive centipede-like predators that feed upon the crabs. If only there were a way to use these creatures to his advantage…

"Trojan Fall"

La Roque has made his big score, now he must get away with it. He is no pilot or spaceman, but he buys a spaceship and heads for the stars, deducing that if he can evade immediate capture then he can make a clean break. With the law hot on his tail, La Roque finds a pair of red dwarf stars, sets his spaceship into the Trojan point between them, turns off all power, and waits for his pursuers to give up and leave. Too late he realizes that his ship has not stayed in the stable Trojan point, but has been drawn into one of the stars. The view shifts to the watching crew on the enforcement cruiser, one of whom remarks that if La Roque had known his science, he would have known that stable Trojan points only exist between objects of vastly differing masses; there is no stable Trojan point between two stars of roughly equal mass.

Fireproof

A saboteur breaks into a space station to destroy it and its nuclear deterrent. He releases fuel into the zero-G confines of the space station and attempts to light it with an incendiary bomb, but in zero-G the floating globs of fuel will not sustainably burn because the globe of flame smothers itself out.

Halo

A superintendent checks on a student's progress. The student has made a real hash of things at the farm, leading to the complete destruction of one plot, and a runaway growth of strange chemicals at the third plot. It's the solar system. The "plots" are planets, the runaway growth on the third plot is all the life on Earth, and these aliens seem to be living comets that farm and eat hydrocarbons.

The Foundling Stars

Elven Toner and Dick Ledermann arrange a fantastic experiment to test their two competing hypotheses regarding star formation, which Toner in particular thinks cannot statistically happen by natural processes without some external impetus. The experiment fails in an unexpected way, and the viewpoint shifts to two "soldiers" (each being mostly incorporeal and several hundred astronomical units large) who are sweeping up interstellar detritus to form stars as part of a galactic war effort. It's them who are providing the needed impetus for star formation.

Raindrop

The Raindrop is an experiment in orbit around Earth. It's a huge volume of water, melted from several comets, encased in a tough plastic skin, and seeded with life forms. The hard radiation of space causes a rapid mutation rate, and the eventual hope is to develop edible life forms that can be farmed and help feed Earth's rapidly growing population.

Silbert is the caretaker of Raindrop, and he's visited by Aino and Brenda Weisanen, a couple who represent major new shareholders of the recently-privatized corporation that owns Raindrop. The Weisanens intend to turn Raindrop into a private home for people like themselves: genetically modified humans who (among other things) can only successfully carry their babies to term in zero-G. Silbert and Bresnahan realize that Raindrop is the hope for billions of people on Earth, and if the Weisanens snatch that hope away by ending the farm experiment, it will cause chaos. But how to convince them to cooperate and come to an agreement that will benefit all of humanity, not just the few hundred genetically modified people who will live in space?

The Mechanic

On a high-speed hydrofoil, our heroes hunt down sick wildlife and treat it. Or rather, not wildlife, but pseudo-life. It's never explained, but the seas are populated by self-reproducing robotic versions of aquatic life, which suffer from various diseases that threaten the new cyborg ecosystem. One of those pathogens attacks the ship, damaging one of the hydrofoils and causing a crash at sea, which injures everyone on board. The rest of the story is about medical technology: they have the ability to use gene sequences and big fancy machines to fix injuries and regrow missing body parts, one cell at a time. One character gets a new face and has a severed hand re-attached and fixed up. It's all bizarre and none of the story hangs together well. This one is disappointing.

The Last Closet: The Dark Side of Avalon

Reviewed date: 2025 Sep 1

613 pages

Moira Greyland tells her life story: how she was abused by parents who were part of the counter-cultural, sexually liberated lifestyle in the 1960, 70s, and 80s. Her father in particular was of the opinion that everybody should have sex with everybody, all the time, and that would make everyone happy. The abuse that grew out of that worldview is unspeakable and unforgivable. (The Christian sexual ethic is really so much better. It just is.)

What makes Moira's story notable rather than just tragic is who her parents were: Walter Breen, renowned writer and expert on the subject of coin collecting; and Marion Zimmer Bradley, best-selling author of fantasy and science fiction and the co-founder of the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA). Breen and Bradley were well-known and involved in fandom, and Breen's sexual interest in little children was well-known in the 1960s, to the point that he was banned from attending the 1964 Worldcon in Oakland. Breen had been caught literally with his pants down with a child, there were multiple known victims, and Breen talked to people about having sex with children, but all that fandom could muster themselves to do was to ban him from attending one convention—and even then there was a lot of grumbling about it. Nobody called the police.

It was not until his daughter Moira turned him in to the police years later that Walter Breen was finally caught. He was arrested in 1990, was eventually sentenced to 13 years, and died in prison in 1993. He had dozens of victims, including but not limited to his own children. Marion Zimmer Bradley was never brought to justice for her crimes of a similar nature.