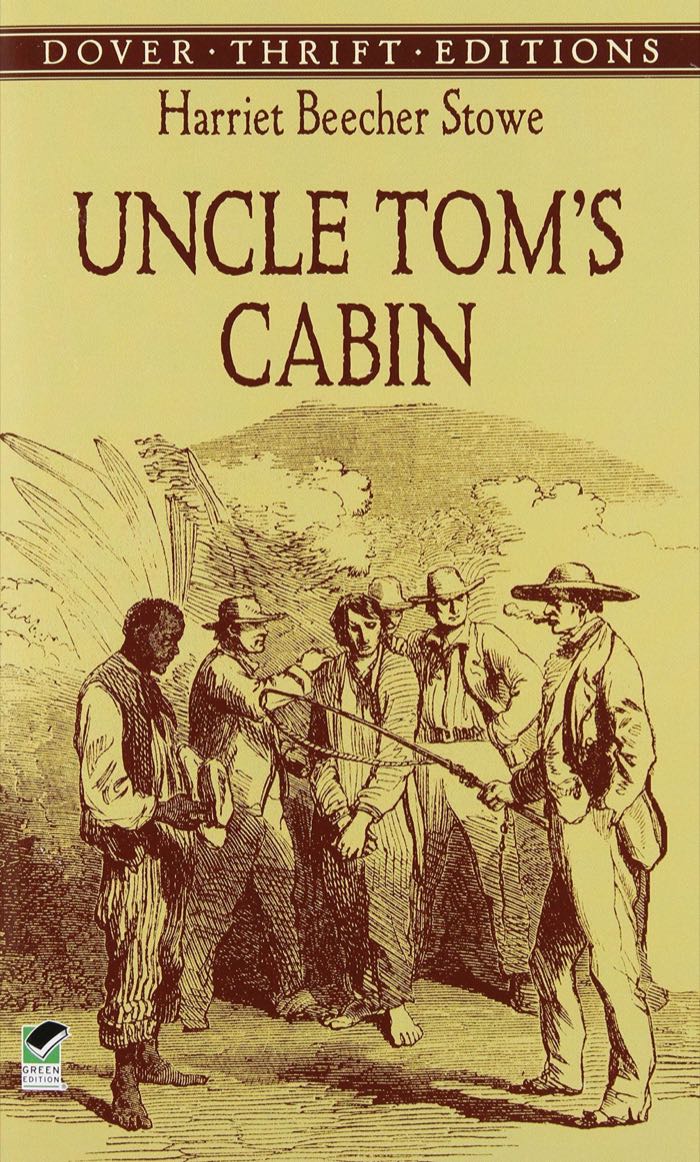

Uncle Tom's Cabin

Reviewed date: 2010 Feb 10

Rating: 2

544 pages

I decided to read one of those classics that everybody knows about but nobody reads. Uncle Tom's Cabin may have helped precipitate the America Civil War, but it's still dreadfully dull in places. Much of that can be attributed to the storytelling style of the 1850s. I suspect that compared to its contemporary competition, Uncle Tom's Cabin is a whirlwind of action.

Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin to show the nature of slavery in America in the 1850s. It was horrific. Northerners and Southerners alike were apt to close their eyes, but Uncle Tom's Cabin reveals the enormity of this crime against humanity and against God.

The story follows Tom, a God-fearing, scrupulously honest slave from Kentucky. His master is relatively kind, but foolishly gets into debt and must sell Tom to a slave trader. The trader sells Tom to Augustine St. Clare, who takes him to Louisiana and employs him as a coach driver. St. Clare abhors the whole business of slavery, but can't see how his actions will change an entire society, so he never gets around to emancipating his own slaves. The real emphasis in this part of the novel, though, is St. Clare's rejection of Christianity. St. Clare sees the wickedness of Southern preachers who twist the gospel to support and celebrate slavery. And he sees the hypocrisy of the northern Christians, who are abolitionists, but won't lift a finger to improve the condition of blacks in America--even as they send missionaries to foreign lands. Tom talks to St. Clare about God and the Scriptures, but St. Clare holds back; not until his deathbed does he come to faith.

But it is too late for Tom. With St. Clare dead, the estate is sold off and Tom is bought by Mr. Simon Legree. Tom's new owner treats his slaves worse than animals. Legree abuses Tom, but cannot break him, for Tom has strength in Jesus. In his anger, Legree beats Tom to death.

Uncle Tom's Cabin depicts the horrors of slavery, which are even more horrible when one realizes that the key events in the novel are drawn from real events. The characters and the storylines are fiction, but the situations and the abuses are real.

The biggest problem I found with Uncle Tom's Cabin is poor choices in naming the characters. A basic rule of fiction is to name each character distinctly. It's best not to have any main characters with similar names; even names that start with the same letter can be confusing. Harriet Beecher Stowe never heard of that rule. There are at least two Toms, and several Georges. I never could keep the Georges straight.

Another problem is that Stowe writes in dialect when the black slaves speak. It's difficult to decipher what they're saying. And, to my 21st century sensibilities, it smacks of racist stereotyping. But besides that, there's nothing racist in the book. Uncle Tom is presented as a tragic hero, not a subservient eager-to-please slave, as people often think. The fact that he refuses to run away is strange, but Stowe attributes that to his sacrificial Christian love. Even in the face of torture, Tom prays for his master to come to Christ. And anyway, it was necessary to the plot for Tom to stay and be martyred; if he escaped or even if he died in an attempt to escape, the story wouldn't have the same punch. The fact that he chose to suffer and die casts him as a Christ figure.