The Quest for Holiness and Unity

Reviewed date: 2022 Apr 17

504 pages

Overall, what I see from this history of the Church of God (Anderson, Indiana) movement is an abiding commitment to Christian unity. There were disagreements about doctrine and practice, as in any movement, but the Church of God as a whole was averse to schism over such things. Occasionally some people and groups left the movement; usually they returned a few years later, and the Church of God people welcomed them back. The commitment to unity is real.

I struggle to understand the antipathy towards denominations, and the rejection of all sectarianism. Today I see ecumenical cooperation as the norm, and the idea of opting out of that in the name of unity seems counterproductive to achieving unity. I gather that ecumenical cooperation didn't exist in the same way in the late 19th century, so perhaps I'm looking at things from a different cultural reference.

I'm also not convinced about sanctification as a second work of grace. So…it sounds like I'm rejecting both foundational tenets of the Church of God movement. Except, today's Church of God (which is forty years removed from the writing of this history book) doesn't believe or teach those doctrines in the same way as the founders of the movement did. I can say I've never heard the doctrine of sanctification as a second work of grace being preached. I've only heard it brought up in the context of discussing Church of God history. So there's that.

Preface

The author says he wrote this book for the Church of God centennial, and thanks a lot of people.

Prologue

The Church of God is a restorationist movement in the sense that it attempts to restore the "essential aspects" of the early church, the "spirit, quality, and purpose" of the early Christians. Specifically, the movement seeks to restore holiness and unity. D.S. Warner left the early holiness movement because there was not an equal emphasis on unity.

There is yet another approach to restoration, which, like most other types, presumes that somewhere in the centuries since the first there have been departures from or neglect of some of the essential aspects of that primitive community. Therefore an attempt is made to reconstitute the early church--not literally--but in spirit, quality, and purpose. It is in this category of restorationists that the Church of God would find the best description of its reason for being. (xi)

1. In the Fullness of Time

The Church of God began in the USA, post-Civil War, in the Middle West. It was a time of westward expansion, urbanization, and immigration from Europe. The culture was changing. Industrialization was occurring. Populism was strong. There was a growing conflict between cultural elites and the rural population. Religion became more populist, less intellectual and liturgical. Churches and society as a whole were explicitly segregated.

2. Religious Reaction: Confusion, Accommodation, and Reform

A grass-roots holiness movement eventually coalesced into organized groups. The Church of the Nazarene came out of (mostly) Methodism. The Church of God adhered to Wesleyan "second blessing" doctrine but did not come out of Methodism and so did not join the Nazarenes. The Church of God also did not insist on tongues or "motor phenomena" and so they were not considered a "left-wing" holiness movement. The Church of God was also not premillennial.

3. Sorting Out the Issues

(1880-1890)

D. S. Warner joined the Winebrennarian Churches of God and preached against sectarianism. Later he became convinced of holiness doctrine and of sanctification as a second work of grace, and began preaching that. He was eventually disfellowshipped and stripped of his license for holding holiness meetings. He joined the Northern Indiana Eldership of the Church of God, and his mission was to "oppose sectarianism and uphold holiness."

4. The "Flying Roll" and the "Flying Messengers"

(1880-1895)

The early days were a frenzy and a flurry of itinerant evangelism. The Flying Roll refers to the Gospel Trumpet magazine, and the Flying Messengers to itinerant ministers. It was the Gospel Trumpet publication which was the center of the movement. Lots of people felt called to preach, disliked sectarianism, and experienced sanctification. They left their denominations and struck out on their own. They were the come-outers. They were held together by like-minded beliefs and by the Gospel Trumpet publication by D.S. Warner. There was also an emphasis in this early movement on divine healing.

Warner's wife Sarah was led astray by a colleague, Stockwell. She withheld sex from Warner, thinking such a marriage was more holy. She and Stockwell tried to convince Warner to sell the Gospel Trumpet Company (the publishing company) to Stockwell, but Warner refused. Later, Sarah left Warner and divorced him. Later, Warner's partner in the publishing company, J. C. Fisher, divorced his wife to marry a younger woman. Fisher left the company and was replaced by E. E. Byrum.

5. A Developing Reformation Consciousness

(1880-1895)

What did this early movement have that was unique? They had no prophet. They didn't preach anything heretical. What they wanted was not just to do a few things different, but to reform the "whole structural system" of the church. They wanted to eliminate sectarianism entirely. They believed:

- The Bible is the only foundation. "No creed but the Bible." The Bible is inspired--not the words or thoughts in the Bible, but the human authors were inspired.

- Religion is experiential. A believer must have a definite, singular experience of salvation. And a definite, singular experience of sanctification, the second work of grace. Full salvation is regeneration + sanctification. Regeneration, the first work of grace, is the removal of past sin and adoption into Christ's family. Sanctification, the second work of grace, is the restoration to a state of holiness, the pre-fall state.

- God's calling "to proclaim and to model the visible expression of His one holy catholic Church." Denominationalism in itself is per se sinful. In particular, formal church membership for clearly unregenerate persons showed the denominations to be flawed. The movement wanted a new, unorganized church with no human organizational structure, led only by the Holy Spirit. This came from their belief that God's church must be unified with real tangible unity, not a nebulous spiritual connection. I.e., invisible unity is no unity at all. Thus, no human organization meant no offices or titles. The only exception was for ordaining elders and ministers. Unity did not extend to requiring complete conformity of doctrine; there was openness to growing in knowledge, and some allowance for differing interpretations of scripture.

- Divine destiny, that is, a belief that the end times were near. Apocalyptic themes abounded, with Roman Catholicism and Protestantism identified as the beasts of Revelation. True Christians would come out of these false religions. Interpretations of scripture always conveniently placed the date of their movement's beginnings--the 1880s--in the final stage of the Revelation timeline.

6. Toward a Worldwide Fellowship

(1882-1909)

International missions, churches in Canada, Mexico, Britain, Europe, and India. Also Japan, some in Australia, the Caribbean, and Egypt.

7. Strengthening the Operational Base

(1890-1917)

Churches were established. The Byrum brothers grew the publishing house (The Gospel Trumpet Company) into a 24-hour, 100-person operation, producing two million sheets a day. In 1898 they moved from Grand Junction, Michigan to Moundsville, West Virginia. In 1906 the company moved to Anderson, Indiana. In 1916 E. E. Byrum resigned as editor-in-chief and was replaced by F. G. Smith.

By 1917 there were many churches with land and full-time pastors, the publishing house was going strong, but there was no larger decision-making body or process. There was still a strong aversion to any man-made organization. Even corporate legal entities were problematic, which made it tricky for churches to legally own land and property.

8. Ethnic Outreach

(1885-1920)

There was specific outreach to: blacks, Germans, Slovaks, Scandinavians, and Greeks. Church of God unity doctrine precluded the idea of segregated churches. The movement was anti-prejudice, pro-integration from the beginning. There was violent persecution for integrated services and preaching. Thus reality made separate, segregated churches a pragmatic choice. This led to locally segregated congregations, a nationally unified church, with parallel structures in between: The National Association of the Church of God for blacks.

Lots of outreach to Germans. Thriving German-language churches and publications until World War 1 led to an decline.

9. Facing Difficult Issues

(1896-1917)

The movement faced two crises related to holiness. The first was about the doctrine of sanctification, and the second was about neckties.

Sanctification is a second definite instantaneous work of grace, subsequent to justification, wrought by faith through the Holy Spirit, which frees human beings from their inherited or Adamic nature, cleansing them from all desire or love for sin and enabling them to live a life free from sin in this present world. (p. 184)

Zinzendorfism, or the anti-cleansing heresy, said the cleansing happened at justification, not at sanctification. This heresy was refuted in 1899; most adherents of Zinzendorfism recanted or left the movement.

The original theological position of the Church of God Reformation movement on sanctification thus remained intact and the controversy subsided. This did not mean, however, that all questions were answered in regard to this doctrine and particularly its implications for daily living. Within a decade the issue of defining specifics regarding the outward signs of a "sanctified life" was to bring in a new round of internal debate, conflict, and eventually schism. The crisis took the form of a controversy of the wearing of neckties. (p. 191)

Schism over neckties: Growing competitiveness in avoiding worldliness led to numerous rules: No tobacco, alcohol, drugs, dances, play parties, collars, cuffs, neckties, etc. This lead to conflicts between rural vs. urban standards of dress. Asceticism was valued, but was there room for disagreement about the specifics? What counted as worldliness and pride? The showdown was about neckties.

A 1911 resolution "discouraged" neckties but did not forbid them. There was an anti-necktie camp, but no pro-necktie camp. The anti-necktie people left not because of disagreements with any pro-necktie people, but because the others--particularly the publishers of the Gospel Trumpet would not come out against neckties, but instead left room for differing opinions. C. E. Orr opposed anything new, left the Gospel Trumpet and started his own publication, the Herald of Truth. Fred Pruitt published Faith and Victory in Guthrie, Oklahoma. That publication later merged with another Orr publication, and remained anti-necktie and anti-Anderson. Through it all, the Church of God never kicked these people out, but continued to list them in the annual Yearbook.

10. Breaking the Organizational Barrier

(1916-1928)

The movement grew too big and needed organization. As needed, the Church of God established a General Ministerial Assembly, a Bible training school, a Missionary Committee, and published a Yearbook of all ministers and congregations. The Gospel Trumpet Company became more under the authority of the church. E. E. Byrum gave up some power. Sunday School, once a "child of Babylon" was established and curriculum published. The church established official boards, that is, ministries:

- Missionary Board

- Board of Church Extension and Home Mission

- Board of Sunday Schools and Religious Education

- Anderson Bible School and Seminary

11. Reassessments Regarding Methods and Ministry

(1917-1935)

D. S. Warner had been anti-seminary, wanting only Spirit-led preachers. Instruction was by informal apprenticeship and community living in missionary homes. These missionary homes, or faith homes, became de facto Bible training schools.

Anderson Bible Training School was established in 1917, using the Trumpet Family building. Theological disagreements almost sunk the college but it survived.

12. The Golden Jubilee

(1928-1935)

Further growth and organization.

13. A Moving Movement

(1936-1946)

Growing Sunday Schools. Expanding, growing colleges, with accreditation. The church supported conscientious objectors in World War 2 (in accordance with longstanding Church of God opposition to war) but most Church of God members served.

Bigger budgets. Some cautious para-church cooperation. Radio programs. More business-like planning, not just Spirit-led. Even--gasp!--voting to make decisions.

Theological re-interpretations of Revelation, as the early movement's apocalyptic beliefs were clearly not working.

14. Mid-Century Pain and Progress

(1946-1954)

Disaffection with national leadership in Anderson.

- Ecclesiasticism and abandoning historic doctrines of unity

- Lowered moral standards of holiness among leadership (E.g., doctors, not divine healing. The publishing house taking on commercial printing jobs.)

- Power bloc: a few powerful leaders called all the shots. (An interlocking board of directors situation.)

- Lack of voice for the little guys and outsiders

- Post-war anti-dictatorship sentiments and growing support for democracy and voting

Watchmen

L. Earl Slacum published "Watchmen on the Wall", decrying the loss of proper teaching on unity and on sanctification, with Anderson as a real problem, with "doctrinal and behavioral laxity" among the leadership. Slacum left the Church of God and started the Watchman movement. However, the movement promptly organized itself just like the Church of God, so Slacum quit, repented, and rejoined the Church of God. (However, the Bessie, OK church never rejoined.)

The Church of God leadership seems remarkably patient with agitators and critics.

The effect of Slacum's Watchman movement spurred the Church of God to look into its organization, and in 1954 a national-level reorganization improved much.

15. Toward Spiritual Democracy

(1955-1962)

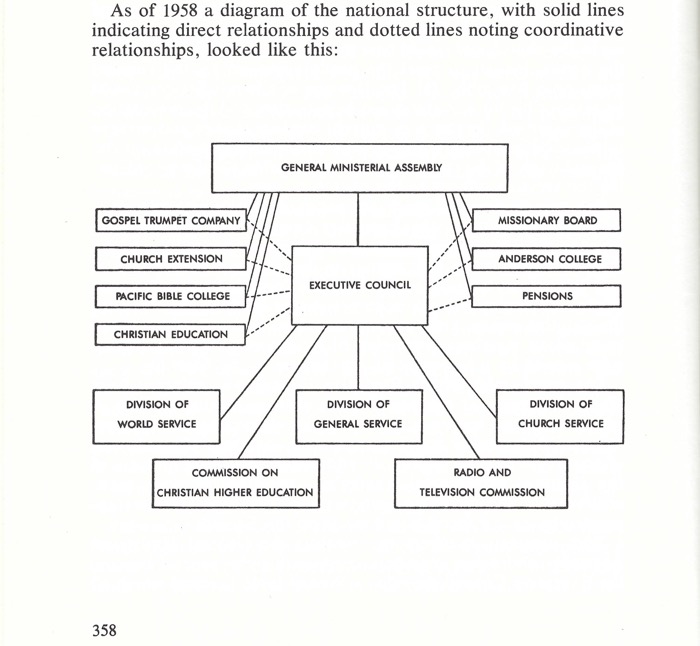

A period of intentional reorganization to expand decision-making and leadership. By 1957, the General Ministerial Assembly conducted its business via seven boards and agencies:

- Missionary Board

- Board of Church Extension and Home Missions

- Anderson College and Theological Seminary

- Pacific Bible College

- Board of Christian Education

- Gospel Trumpet Company

- Board of Pensions

In addition, the Executive Council conducted church business through the 1) Division of World Service, 2) Division of General Service, and 3) Division of Church Service. Other work was done through the Commission on Christian Higher Education, and the Radio and Television Commission. (See the organizational chart.) The major innovations in organization were the Executive Council membership: the 3 officers of the General Ministerial Assembly, one member each from the 7 boards, and 16 members (who could be lay persons, and could not be employees or officers of the boards) elected by the General Ministerial Assembly. This helped break up the leadership blocs.

The Church of God also made real and tangible commitments to racial integration. A committee on racial integration recommended more integration, cooperation, and the elimination of duplicate state ministerial assemblies. (And to my surprise, the Church of God acted on these recommendations. Good for them.)

The Gospel Trumpet was renamed Vital Christianity, and the Gospel Trumpet Company become Warner Press. Anderson College grew. Pacific Bible College grew and became Warner Pacific College. In 1960 the tabernacle at Anderson collapsed, and a new Warner Auditorium was built. The Church of God made moves and changes to allow greater input from the field, that is, everyone not in Anderson.

16. From Congress to Consultation

(1963-1972)

The Church of God worked "toward a more participatory manner of decision making." There was no numerical growth, except at the college. Budgets grew. Real work on integration and race relations began in 1964--this was real progress, with an ongoing commitment. The Church of God began having conversations with other denominations. The General Ministerial Assembly was renamed the General Assembly.

17. Target: Centennial

(1972-1980)

Continuing integration, elevating black voices and black people, funding black ministerial education, integrating the assembly, setting up channels to hear concerns, and evaluating progress.

The commitment to supporting pacifists and conscientious objectors continued.

Review of ministerial training/ordination standards lead to more focus and money to education, specifically the seminary.

The Church of God cooperated in the ecumenical Key 73 plan to share the gospel with every American household. There was a push for growth, with an emphasis on Latin America in the 1970s, with plans for similar goals in Asia in the 1980s.

Continuing attempts to get more lay-persons involved in leadership.

Established a committee to study doctrine, with a focus on specifically those areas that might divide the church. The Church of God universally held: "(1) to be a genuine Christian one must have a life-changing relationship with God. (2) The church is both human and divine and is composed only of true believers. (3) Christian unity is to be sought."

Speaking in tongues divided some churches. Mostly it was permitted but not encouraged, and most of all should not be allowed to divide people.

There was some national-level and international-level ecumenical cooperation.

18. Toward the Second Century

How to organize when the Church of God does not believe in human organization? The Church of God organization is not episcopal, presbyterian, or congregational, but an amalgamation of all three. And there is not enough lay involvement in the leadership.

The rise of ecumenicalism--which the Church of God largely did not participate in--makes the unity message and doctrine of the Church of God kind of useless. (This sometimes lead to the Church of God criticizing ecumenacalist methods rather than seeing the benefit of ecumenicalism.)