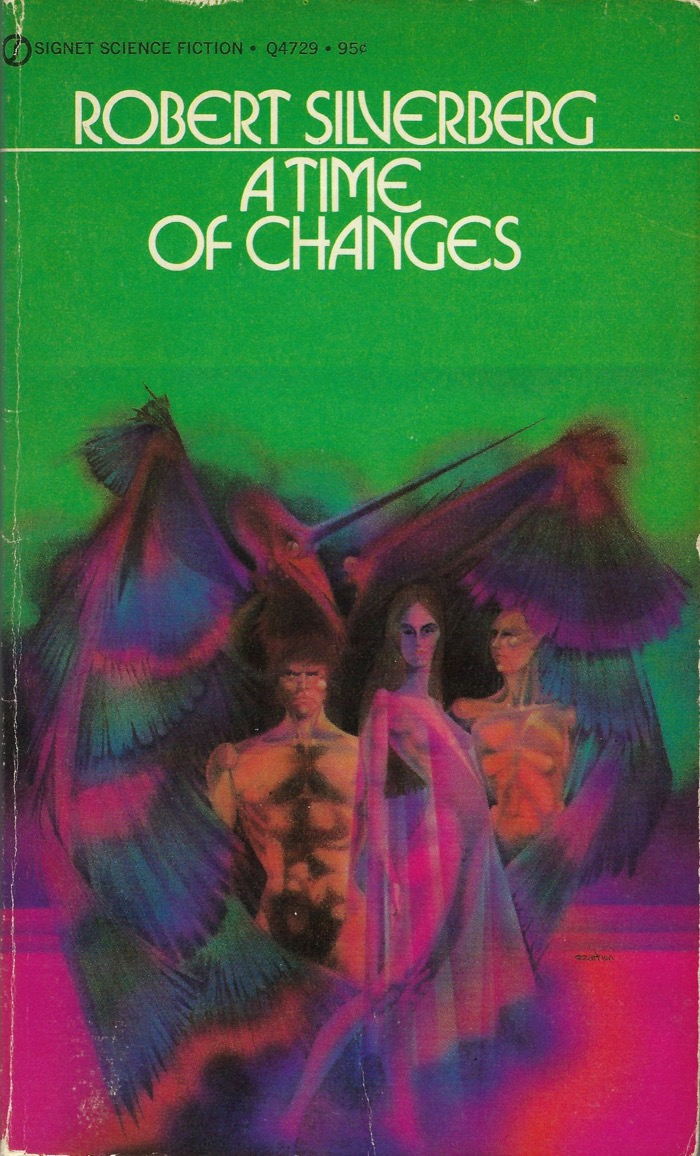

A Time of Changes

Reviewed date: 2018 Mar 2

Rating: 2

220 pages

A Time of Changes reminds me of The Birth of the People's Republic of Antarctica. Both are told as the memoirs of a man looking back at his life, recounting the events that lead up to the awful reveal: the monstrous sin for which he is infamous, which all the world except the reader already knows.

Both stories feature unlikable protagonists, Kinnall Darival and Grim Fiddle. Both men spark social upheaval, leave human wreckage in their wake.

The difference is that in A Time of Changes, Robert Silverberg actually creates an interesting cultural setting for the story.

The people of Borthan live by the rules of the Covenant. Baring one's soul, revealing one's feelings, is utterly forbidden. Even using the personal pronouns--I, me--is the worst kind of filthy speech. This is not simply a custom, it is the law. Self-baring is a crime.

But for all the talk of self being anathema, the Borthan culture seems fixated on matters of self. And of everyone, Kinnall Darival, the second son of the septarch of Salla, is the most unbelievably arrogant and self-centered. He never outgrows an adolescent obsession with his bond-sister Halum, which he mistakes for love. In fact, Kinnall loves no one but himself. He uses women without considering it. He marries Loimel because she looks like Halum, never caring or considering what this does to Loimel--or to Halum.

Kinnall wouldn't know chastity if it bit him. He sleeps with prostitutes, degrades them with foul words and deeds, without a shred of awareness that he is abusing them. He never considers being faithful in any way to his wife Loimel, never thinks to consider how his actions affect her. Women are to be used.

Kinnall never grows or changes. He meets an Earthman, Schweiz, who introduces him to a drug that opens the mind and allows a telepathic sharing of thoughts when taken with a partner. Kinnall takes the drug and it opens his mind to others, but he doesn't learn from the experience. For him it is a selfish addiction. He shares the drug with anybody, everybody, with no consideration for them--and for most people, the drug is a painful and horrifying experience. But although the drug opens his mind, Kinnall doesn't learn to truly share himself with others or make genuine human connection. He destroys others to satisfy his own needs. He cannot see beyond his own need for another hit of the drug.

Kinnall, in his arrogance, cannot even be truthful to himself. He imagines his drug-sharing to be a holy crusade. He is a prophet crying out in the wilderness, leading his people into a better way of life. But actually, he is spreading hurt, pain, and destruction to satisfy his own fleshly cravings. There is an emptiness in his soul and he tries to fill it by taking from other people.

The people closest to him are those he hurts most: his bond-brother Noim is afflicted with horrific nightmares after trying the drug. Kinnall shares the drug with his bond-sister Halum, and it drives her to suicide. The book closes with Kinnall banished to the Burnt Lowlands, furiously scribbling his memoirs as the Septarch's search party closes in on him, to bring him to justice.

I don't think my take on Kinnall's character is exactly what Silverberg had in mind when he wrote the book, but I'd bet fair money that Silverberg wasn't setting Kinnall up as a completely reliable narrator, either.

Overall, I'm not surprised this got nominated for the major prizes. And I'm not surprised that it won the Nebula but not the Hugo. It has some great ideas, but also some truly boring bits: way too much description of geography. And Kinnall drones on and on about himself, but there's very little meaningful action. Still, not overall a bad book, but it's not one I intend to re-read.