The Beasts of Tarzan

Series: Tarzan 3

Reviewed date: 2017 Dec 12

Rating: 3

159 pages

Unlike the previous book, this time Burroughs doesn't waste time with Tarzan as a Parisian gentleman or his service as a spy in Algeria. He dumps Tarzan back into his element: the savage jungle of Africa.

Rokoff and Paulvitch have escaped again, and their first thought is revenge. They kidnap Tarzan's son, little Jack Clayton. Paulvitch shaves off his beard, a disguise so complete that Tarzan fails to recognize him, and lures Tarzan into a trap. Rokoff and Paulvitch lock Tarzan belowdecks on the steamer Kincaid, and set sail for Africa.

Rokoff doesn't kill Tarzan; he strands him on a little island off the coast of west Africa. Rokoff explains his revenge in a note:

"This will explain to you" [the note read] "the exact nature of my intentions relative to your offspring and to you.

"You were born an ape. You lived naked in the jungles—to your own we have returned you; but your son shall rise a step above his sire. It is the immutable law of evolution.

"The father was a beast, but the son shall be a man—he shall take the next ascending step in the scale of progress. He shall be no naked beast of the jungle, but shall wear a loin-cloth and copper anklets, and, perchance, a ring in his nose, for he is to be reared by men—a tribe of savage cannibals.

"I might have killed you, but that would have curtailed the full measure of the punishment you have earned at my hands.

"Dead, you could not have suffered in the knowledge of your son's plight; but living and in a place from which you may not escape to seek or succour your child, you shall suffer worse than death for all the years of your life in contemplation of the horrors of your son's existence.

"This, then, is to be a part of your punishment for having dared to pit yourself against

N. R.

"P.S.—The balance of your punishment has to do with what shall presently befall your wife—that I shall leave to your imagination."

Tarzan presumes his wife is safe in London, but Jane has been kidnapped as well. With the help of Sven Anderssen, the Swedish cook, she escapes with the baby. Jane, the baby, and Anderssen set off through the jungle.

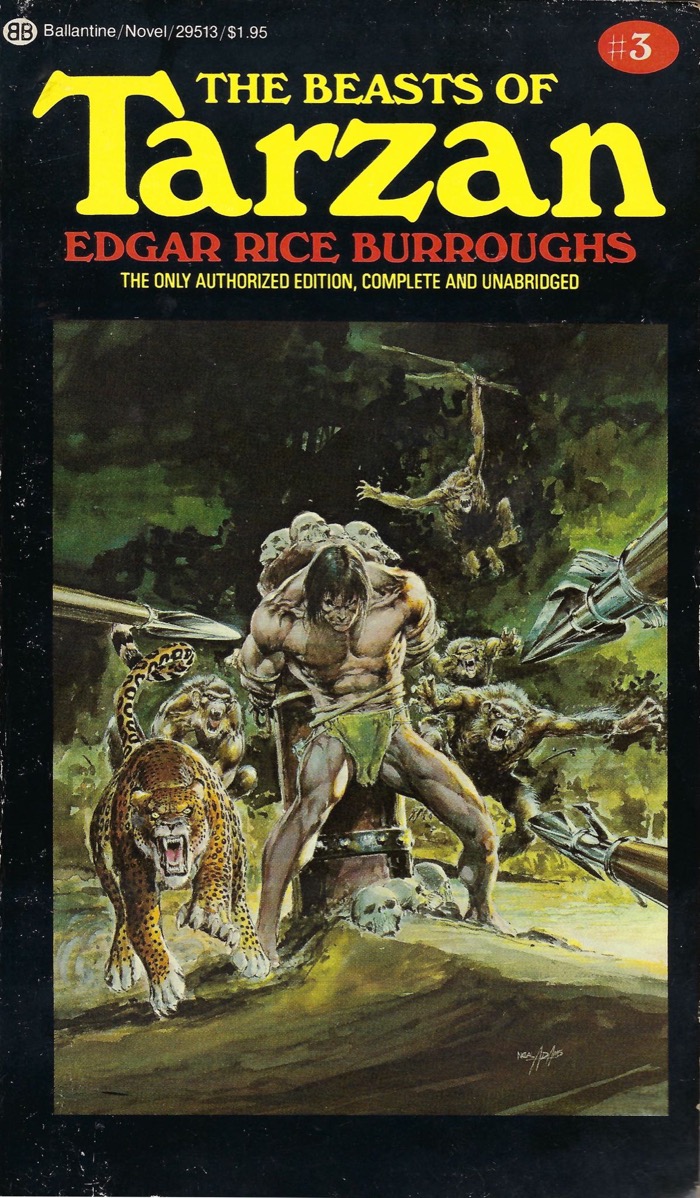

Meanwhile, Tarzan is gathering his beasts. He finds the island inhabited by a tribe of apes, whose loyalty he wins. He also saves the life of Sheeta, the panther; the cat and Tarzan develop a real friendship. And Tarzan picks up Mugambi, chief of the Wagambi. Yes, a black African man is one of Tarzan's retinue of jungle beasts. So if you were hoping for less racism than in the previous book, well, try to enjoy the story anyway.

Tarzan and his beasts escape from the island and pursue Rokoff, who is pursuing Jane. Eventually they all end up together in a big confrontation on the Kincaid, where Sheeta kills Rokoff. Paulvitch is left alive in the jungle, presumably never to be seen again. I doubt he'll stay gone.

The baby dies and is buried in a jungle village, but it turns out the baby isn't Jack. Nobody knows where Jack is, or how this baby got to be on the Kincaid.

When Tarzan and Jane get back to London, they learn that Jack was safe the whole time. Paulvitch had double-crossed Rokoff and substituted the infant with an orphaned child. The real Jack had been ransomed back to the Greystoke household during Tarzan and Jane's absence, and been cared for by his nurse Esmerelda.

Noble beasts and fearful men

I noticed that whereas Tarzan's beasts--the ape Akut and his fellows, and Sheeta--are brave and noble and at home in the jungle, the African tribesmen that Tarzan encounters are anything but. They are cowardly, fearful, wicked, deceitful, and most of all, terrified of the savage, wild world they inhabit.

At first, it seems that Burroughs is describing these people as lower even than the beasts. Maybe he meant it that way. Tarzan as least holds this opinion, but we sort of expect Tarzan to identify more with beasts than with men. That's the whole conceit.

But I can't help being reminded of the Machiguenga people as described in Ron Snell's books. (It's a Jungle Out There, Life is a Jungle, and Jungle Calls.) He grew up among the Machi tribe in the jungle of Peru. The people there, although they lived in the jungle, lived in fear of it--much like the fear Burroughs describes. They feared the spirits, they feared the unknown, they feared everything. This isn't a symptom of men being less than beasts, it's because people are more than beasts: humans have a God-given sense for the spiritual. And when we don't know God, we imagine capricious spirits behind everything. And we fear. That's why we need God and the gospel. The jungle may be a dangerous and unhealthy place to live, but it doesn't have to be a fearful one.

Burroughs wasn’t making a spiritual observation, though. He was just being casually racist.