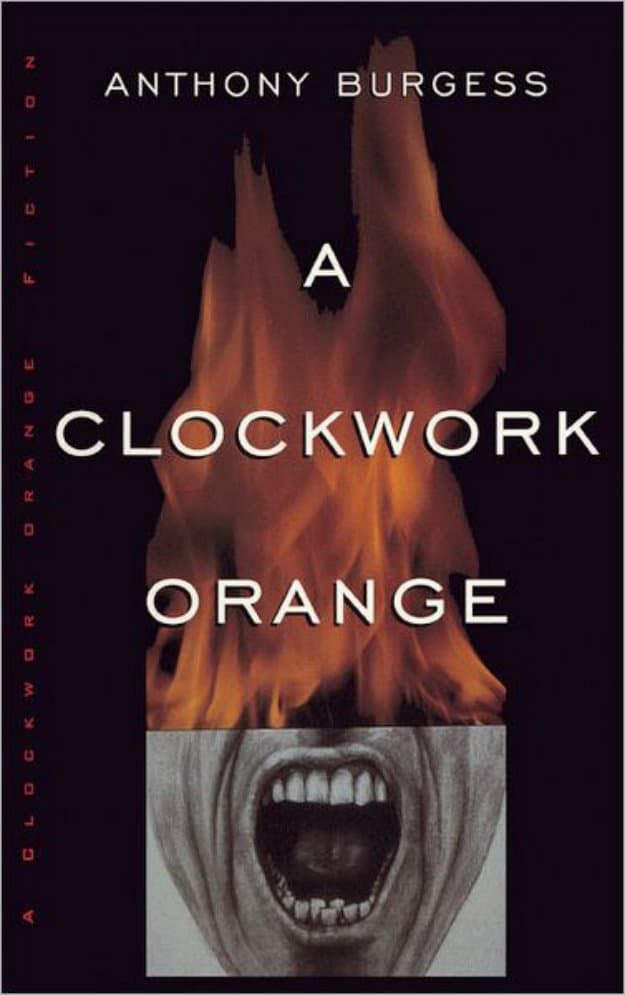

A Clockwork Orange

Reviewed date: 2005 Jan 07

Rating: 4

192 pages

It seems priggish or pollyannaish to deny that my intention in writing the work was to tittilate the nastier propensities of my readers. My own healthy inheritance of original sin comes out in the book and I enjoyed raping and ripping by proxy.

Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange Resucked

Fifteen-year-old Alex likes nothing better than violence and crime. His only pleasures in life are wanton destruction. But he gets caught--and sentenced to prison for murder. There, in prison, the government experiments on him: psychological conditioning renders Alex incapable of violence. In effect, his capacity for evil is removed. The new reformed Alex is no danger to society, but is he truly human? What is the true cost of denying a man free will?

Nadsat: Alex and his droogs talk in a slang known as nadsat. It is the street language of the teenagers, and besides having a slightly different grammar, it uses many foreign words, mostly borrowed from Russian. It requires careful reading at first, but one quickly picks up on the new words.

Violence: A Clockwork Orange is violent, and must be so. Alex chooses sin, and Burgess describes his actions. It must be this way; to censor the book would be to cheapen and lessen the moral: that morality is a choice. Fortunately the worst parts are softened by the use of nadsat: foul language and obscene imagery are rarely so shocking when rendered in a foreign language.

Chapter 21: The first American editions of A Clockwork Orange omitted the 21st chapter. While you can read the book this way, it becomes nothing more than an exercise in violence and sexual perversion. The 21st chapter shows the transformation of Alex, and is, according to Anthony Burgess, the essential piece that completes the book as a work of literature. Without it, A Clockwork Orange is a cheap fable. Please, if you read A Clockwork Orange, find an edition that contains the 21st chapter.

A Clockwork Orange rates a strong four.