The Merman's Children

Reviewed date: 2012 Jun 18

Rating: 2

252 pages

Anderson is not at his best when retelling ancient stories, but he sure likes doing it. In The Merman's Children, Anderson shows us the last days of faery, where only a few creatures of magic still survive amid the inexorable tide of European Christendom.

In particular, the merfolk of Liri are driven out when a priest exorcises them from their coastal home in Denmark. The merfolk decide to try for the New World, where Christendom has not reached. They fail; a storm turns them back, and they end up in Dalmatia. There, the only options are extinction or assimilation. They choose assimilation--choosing to follow Christ and embrace Christianity. God grants them souls, and in an act of mercy, permits them to retain--albeit dimly--memories of their pre-conversion lives.

Anderson presents the merfolk not precisely as sinless, but rather, amoral. They lack souls, ergo, they cannot sin. Lacking souls, their lifespans are unlimited, although they can die from accidents, injury, or disease. And when they die, they simply cease to exist--no soul means no afterlife.

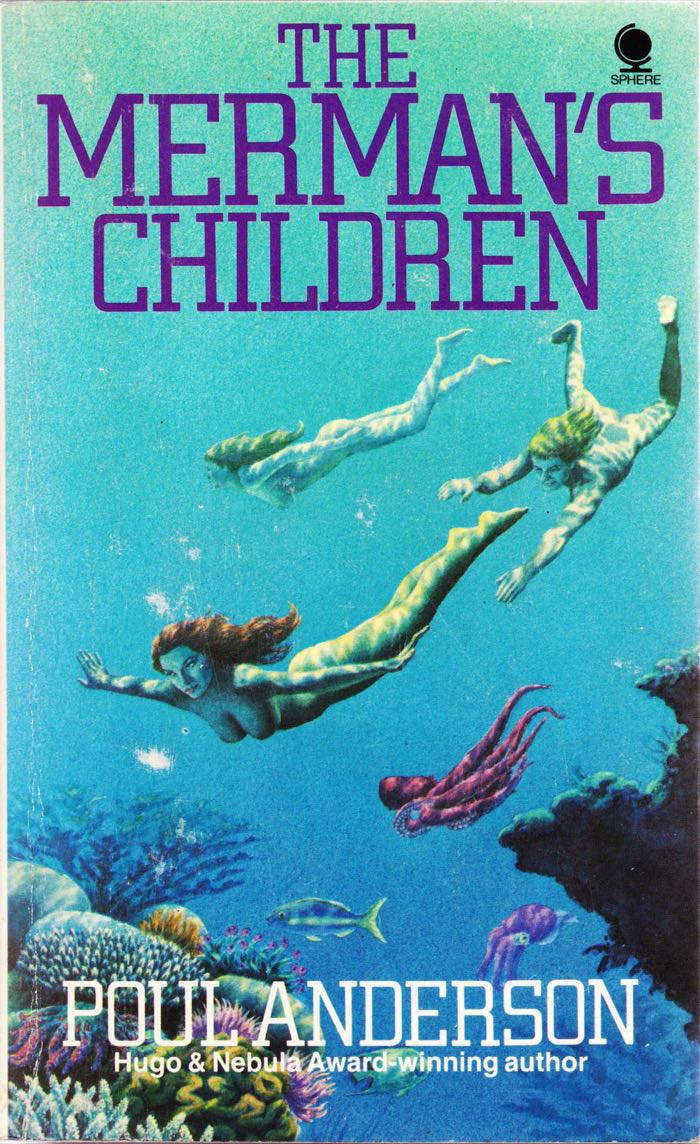

In consequence, the merfolk have no taboos about nudity or sex. Nakedness is natural, and they have sex nearly as casually as they have a conversation. I'm not sure if Anderson means to suggest that this is the natural state of an unfallen race--certainly the nakedness suggests a state akin to Eden. But I'm not sure that's exactly what he's going for.

I didn't find the book completely satisfying. In particular, Anderson seems to imply that the faery custom of nakedness and sexual freedom is superior to the Christian mode of clothing and monogamous marriage. On the other hand, within the context of the book, the power of God and of Christ are very much real. Even the merfolk recognize the truth of God as the creator, and Jesus as the redeemer. (It's just that, being soulless and therefore morally incapable of either sin or obedience, the merfolk have no need for a saviour.)